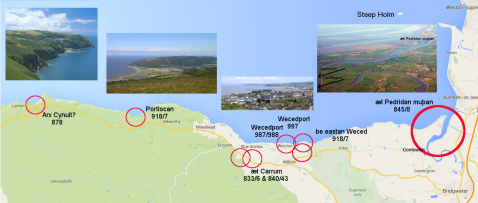

The site of the battle of arx Cynuit, 878 AD: at Countisbury or not?

The argument for COUNTISBURY

1. Countisbury is in Devon – as was arx Cynuit, according to Asser and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Domnania, Defenascire)

2. The name Countisbury might derive from something like Cynuits-burh

3. Wind Hill promontory fort at Countisbury is surrounded by high cliffs and a river gorge and is therefore tutissimus on all sides, except the east – exactly Asser’s description of arx Cynuit. This is the most persuasive argument, along with 4

4. The fort has a rampart (mœnia nostra more erecta) on the vulnerable, eastern side – Asser again, perhaps meaning ‘as the Welsh built them’, with a bank and ditch?

And that’s the evidence, I think.

The argument against COUNTISBURY

1. Landing: The contemporary accounts (Asser and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle) say that the Saxons were forced into retreat by a Viking force, reportedly of 800-1200 men. ‘Arx Cynuit‘ was where they took refuge, and where they were besieged by the Vikings.

At Countisbury, the precipitous cliffs (north) and the gorge of the Lyn and East Lyn rivers (west and south) made the hillfort inaccessible, tutissimus on three sides.

So, where did this fleet of 23 ships with at least 800 men on board land so as to position themselves on the eastern side of Wind Hill, just outside the rampart, a good 700 feet above sea level (see note 1 below)?

If the Saxons retreated into the hillfort, they would have entered it on the eastern side which is where the only entrance was. So the besiegers must have been further east again, following them westwards and then settling in front of the rampart to starve them out.

2. Viking raids: There are no records of any Viking raids on this coast further west than Porlock, which is about 10 miles away to the east (most dates a bit uncertain):

833 [836] Danes raided Carhampton(?) in 35 ships and defeated King Egbert

840/841 [843] Another(?) 35 ships landed at Carhampton(?) and defeated King Æthelwulf

845 [848] A raiding party was defeated by Eanwulf, ealdorman of Somerset, near the mouth of the R. Parrett (maybe after landing near the harbour at Combwich

[878 arx Cynuit – 23 ships landed but the invaders were defeated]

914/915 raids east of Watchet and then Porlock

988 a raiding party sacked Watchet

997 Watchet again sacked

And when the banished Harold Godwinson sailed back to Britain from Ireland in 1052, he landed – at Porlock, and looted it while he was there.

What all these raids have in common – Countisbury is the odd one out – is that they were all at precisely identified places on easily accessible parts of the coast, where there were low-lying beaches and harbours; and these raids went no further west than Porlock Bay, at which point the precipitous cliffs began. So, did the Vikings land at Porlock and advance on a Saxon fyrd which then ran away, for 10 miles, until they reached the Wind Hill fort at Countisbury?

3. Viking aims: Although the Vikings eventually began to settle in Britain instead of carrying out lightning raids, there was no sign as yet (in 878) of attempts to settle in this part of the country. It seems that up until the end of the 10th c. they were content to raid, loot and kill here. And this poses another difficulty for locating arx Cynuit at Countisbury: what were they hoping to raid?

This was (and still is) among the most remote, bare and inaccessible parts of the British coast. There’s little sign of Roman occupation, and not much sign of the Saxons.

Exmoor: still wild and unpopulated

Further east, there were royal estates at Carhampton, Williton and Cannington and there would have been some kind of military presence there: thegns tasked with protecting the king’s interests; Watchet became one of King Alfred’s burhs – and of these four centres only Williton escaped the raids. But to the west from here there was little more than some smaller settlements and abandoned Iron Age hillforts. Little or no spoil for considerable effort.

And what would a band of Saxon thegns, presumed to be several hundred strong and fully armed (since they eventually slaughtered most of the enemy army), have been doing there, far from the royal estates? Had the Vikings landed at Porlock and marched westwards, away from the rich plunder of the eastern settlements, to Countisbury where the Devon detachment happened to be gathered (unsupported, apparently by any source of provisions)?

A slightly later version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the chronicle of Æthelweard, has a brief report of the incident, and he was first to introduce the name of Odda, ealdorman of Devon, as commanding the force (which would presumably, therefore, have been part of the shire fyrd). However, Æthelweard can’t be entirely relied on – according to him the Vikings won the ensuing battle. Nevertheless, the story persisted that Odda was the man in command and, since all other versions confirm that the Vikings were defeated, Odda was transformed into the victor rather than the vanquished.

The main questions are why would the Vikings choose this difficult area to invade with nothing obvious to plunder? and what was this fairly substantial armed Saxon force doing in the middle of nowhere?

4. Archaeology: The archaeologists report that there are no signs of settlement or any 9th-c. reoccupation of the Wind Hill fort at Countisbury.

5. The name: There have long been doubts as to whether the name ‘Cynuit’ can be the derivation of ‘Countisbury’. Though many things are possible, names of similar origin develop quite differently. Cynuits-burh would not become Countisbury [Old Somerset has suggested the common Celtic toponym ‘condate’ – a confluence – as an alternative, based on the British settlement overlooking Watersmeet].

6. Water: Asser specifically stated that there was no water close at hand on arx Cynuit, so thirst was a risk for the Saxons. However, there is certainly a spring on Wind Hill now. Not a strong point but it doesn’t support the Countisbury case.

7. Devon: Arx Cynuit may not even have been in present-day Devon as the position of the Somerset-Devon border at that time is unknown. Or it may have been, as a persistent legend has it, on the west Devon coast near Appledore, not the uninviting north.

Conclusion: Although many modern scholars have expressed no doubt that Countisbury is the site of arx Cynuit, other scholarly sources indicate it as no more than one possibility among several. Old Somerset is among the sceptics.

More archaeological evidence would be valuable. Although those precipitous cliffs must have been a temptation for a mass dumping of 800 slaughtered Vikings, recent evidence has suggested that in the 10th c. the Saxons decapitated and stripped their Viking victims before burying them in a pit. Given that – IF Countisbury is the correct location – the exact site of the battle is known, has it ever been excavated? Rhetorical question. But it hasn’t.

Note 1: This quote is from the Exmoor National Park website: “The Exmoor shoreline is the most remote in England. Because of the height and steepness of the cliffs, there is no landward access to the six mile stretches of shoreline from Combe Martin to Heddon’s Mouth and Countisbury to Glenthorne and there are few places where you could land even a small boat.”

“Exmoor has the highest coastline on the British mainland. It reaches a height of 314 metres (1350ft) at Culbone Hill. However, here the crest of the coastal ridge of hills is more than a mile from the sea. If a cliff is defined as having a slope greater than 60 degrees, the highest cliff on mainland Britain is on Great Hangman near Combe Martin. The coastal hill is 318 metres (1043 ft) high with a cliff face of 250 metres (800ft).”

You must be logged in to post a comment.