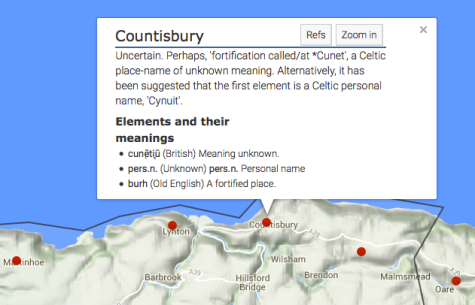

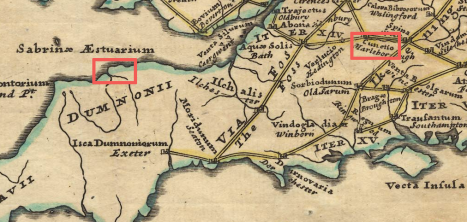

Doubts are sometimes expressed as to the location of Spinae, the penultimate station of Iter XIV. Is it Speen, Berkshire, on the outskirts of Newbury, Spone in Domesday?

The Nottingham toponymists consider the origin of the name to be unclear, ‘possibly, ‘wood-chip place’, from spōn (Old English), a chip, a shaving of wood; perhaps also a wooden shingle tile’. They make no mention of Spinae which in Latin would mean thorns, not woodchips.

There may also have been lingering doubts on account of the fact that no Roman settlement has been discovered at Speen, unlike at Isca, Venta, Aquae Solis, Verlucio, Cunetio – and the final station, Calleva (Silchester), main centre of the Atrebates.

The earliest recorded name for Speen seems to be Spene, perhaps of the 9th century; though intriguingly, the twelfth and thirteen centuries yield Spenes, Spienes and Spenis which look like plural forms, as is Spinae. Faute de mieux, the identification stands. In any case, it is not here so much a matter of identifying Spinae as on checking how accurate the Itinerary is overall in its measured distances.

Do the distances correspond with those given by the Itinerary? Spinae was supposedly midway beween Cunetio and Calleva, xv mpm, or 22.2 km from both; so Cunetio to Calleva is therefore roughly 44.4 kms: how accurate are the Itinerary‘s distances? The conjectural (another variable) road from Cunetio-Spinae-Calleva is, indeed, about 44.5 kms.

However, the two sections are not quite equal: Cunetio to Speen, following Margary 53, is nearer 25 km, whereas Speen to Calleva is barely 20 km.

Thatcham, a little further on from Speen on the main road, has also been suggested as being Spinae. There was seemingly a small Roman settlement there – and even now a ‘Roman Way’. However accepting that suggestion would increase the Itinerary‘s discrepancy, adding about 5km to Cunetio to Speen/Thatcham, making it about 29km; and removing 5km from Thatcham/Speen to Calleva, making that about 15km. That looks out of keeping with the general accuracy of the Itinerary.

The individual sections so far considered (note, the distances Venta-Abone-Traiectus-Aquae Solis have so far been omitted for later consideration) are recorded in the Antonine Itinerary as totalling 109.52km, while the conjectural road route would be 106 km. That is impressively close. Only one stage (Verlucio to Cunetio) falls significantly short of the Itinerary‘s distance, and is the main reason for the overall discrepancy. Strange, since the route from Verlucio to Cunetio seems very ‘straight forward’ and therefore could have been expected to be very accurate:

These results suggest the Itinerary was accurate, discounting the many imponderables and small compensating discrepancies, to within a very few kilometres. So, to the final puzzle: what of Abonae and Traiectus?

You must be logged in to post a comment.